In Kauai, the quiet hits you like an anechoic chamber, a contraption that you may have seen on Nova—of a thing that cuts out all noise from the environment so that you only hear your stomach churn and your heart beat in iambic pentameter. Here, silence is so thick that you hear your muscles flex, your food travel glibly down your alimentary canal and the stream of warm blood rush through your veins with alarming velocity. Buddhist monks in Bhutan or Cambodia speak of these occurrences, of how silence can make you hyperconscious of the microsounds of your own body.

In Kauai, the quiet envelopes in a way that it does not in Maui. Returning to Maui for the 8th time in two decades, I couldn’t help but think of it as an extension of the Sunshine State, a Florida 2.0. Expansive in its picture-perfectness, the sun always shines here and people from all places frolic under the balmy sky. The familiarity of home coupled with the perfection of beauty is what Maui promises and this is what you get.

Hawaiian Monk Seal

Not so in Kauai where the mood and the ambience are quite different. Here, the tone hangs lush. Here, the children look flushed and happy in the hot sun. They will not be over-managed or heckled into submission. Instead, they are self-absorbed in the natural world, staring down the large monk seal that has washed up in a sorry heap on the shore. They maintain a foot’s distance as they witness the fold of the seal’s skin hooding it like a reclusive monk in its cowl. There is no reliance on electronic devices here, no twitching to its alerts, no jerking to its commands. The children here look rugged and happy, the kind who bite into a tart granny apple to stave off hunger and observe the grittiness of the black sand under the still-soft soles of their feet. If there is a correlation between quietude and wellness, it is here.

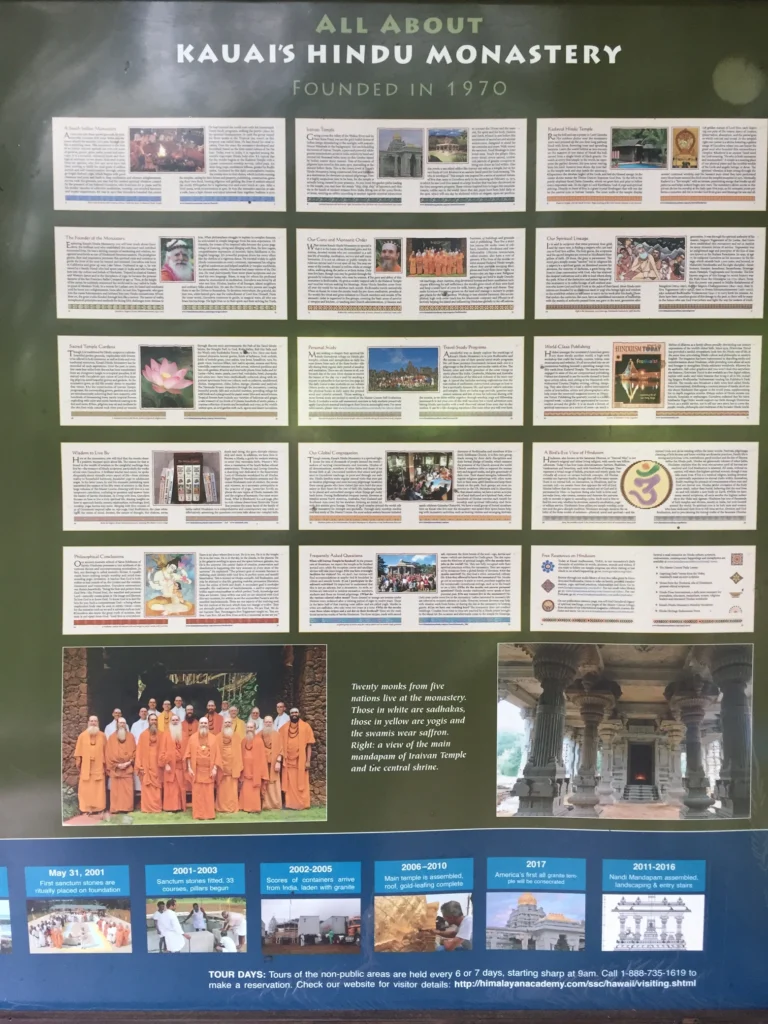

The Iraivan Hindu Siva Monastery on the Wailua River in Kapa’a is no different. It too reflects a similar vibe: the air hangs thick with years of practiced self-reflection and meditation, just as the century-old banyan tree does, straggling its genealogy in its roots. It is the monks of the monastery that President Clinton consulted when faced with national censure and the possible removal from office in the 1990s. And it is to the blessings of this timeless peace that Clinton returned when he was impeached. There is no judgement in silence. Only a large space in which the mind is allowed the freedom to think about its misgivings.

Photo Credit: Raji Writes

Learn more about the Iraivan Hindu Siva Monastery and Rudraksha Forest

In the rudraksha forest, the only one of its kind in America, one traces the trample of footsteps deep in the undergrowth. A lot of walking has been done in these places, a lot of churning over the stuff of life to get over to the other side. People of all ages come here to get perspective—to ask the What If questions. What if things had been different? What if one had taken the path not chosen? Monks in white robes, young ones, middle-aged ones, tread softly in the forest. Visitors talk among themselves or look upward at the trees, snarling Van Gogh-like, upward into a cumulous sky. How do we find relief from the mind? How do we get across to the other side?

Photo Credit: The Hiking HI

Learn more about the Kalalau Trail

I had read Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational several years ago in one of my Design Thinking classes. And I remember being surprised by the recognition that all things of value are determined only in the comparison of it. That the human mind bears witness to one’s truth only in terms of relativism or comparative analysis. In comparison to Maui, say, I prefer Kauai and its absence of frenetic energy. Relative to Maui, for instance, I find it easier to still the mind in Kauai. Everything is on overdrive in Maui—but only by comparison. There, playtime and beach time are scheduled into one’s calendar while Kauai allows for the next moment to reveal itself.

Photo Credit: The Hiking HI

Learn more about the Kalalau Trail

We were in Kauai with our daughter, Priyanka, and son-in-law, Chris. Between the two of them, they had crisscrossed the entire length and breadth of the island several times over. Out hiking on the Kalalau Trail on the Napali coast, they were undeterred by the warning sign posted in clear sight: “The ground may break off without warning and you could be seriously injured or killed.” Perhaps it’s the thrill of extreme adventure or the adrenaline rush of inhaling cool, pristine air, I can’t fathom what it is, but they seem to veer toward experiences that border on the edge of nothingness. They are bent on self-discovery and they return to nature to find answers.

Photo Credit: The Hiking HI

Learn more about the Kalalau Trail

Out hiking on the fabled Kalalau Trail, an 11-mile stretch of difficult terrain that typifies a savage beauty, they are unafraid to bear down on Crawler’s Ledge. This is a clearing that is only 1 to 2 feet wide with sheer rock faces on one side and the crashing ocean hundreds of feet below. The Daily Beast (2019) put the number of deaths from falls off the ledge at 100 in that year alone. This is the same precipice where the nolo or black Hawaiian noddy rests comfortably, away from predators. They are all alone in the world, facing sea and surf on this impossible ledge. But they also look self-sufficient, almost pridefully so, standing apart from the whirling predators high up in the sky or close to water. In recent years, the US Park Rangers are said to have closed these trails because of the deaths of 100 swimmers who have drowned and 85 hikers who have fallen off the ledge. But the nolo is exempt from this possibility. It can fly away at will.

Learn more about Waimea Canyon

Priyanka and Chris are ultra-marathoners and long-distance bike riders. They are the sort who routinely bike 100k on weekends just for the fun of it. In Kauai, they know the easy feeders of bridle paths that veer off peoples’ backyards and gardens. They know where to go and what to do which makes them ideal guides for willing tourists. And with them, we hike. We do easy runs in Waimea Canyon, where the geography looks like a serving of raspberry ice cream, scooped atop a platter. In its verticality, Waimea Canyon resembles the Grand Canyon, except why was it that I had not heard of these Kauaian canyons before arriving here? We slip and slide on treacherous walkways, through waterfalls, on inclines that are devoid of bugs or snakes. We hear a warthog in close quarters. But strengthened with group resolve, we walk on. Foot falling, heel rising, we repeat this step a million times over.

Learn more about Mark Zuckerberg’s Kauai home

I want to say that the natural beauty in Kauai is democratic. Most beaches (except for Mark Zuckerberg’s property ) are public land and open to all. The coastline stretches as far as the eye can see, all 111 miles of it, mostly available for all and sundry. Fourteen hundred acres of this coastline belongs to Zuckerberg—his $270 million home on Kauai’s sealine—but the rest of it is public. It is open to the blue-tarped shanty dwellers sleeping in the uproar of the ocean’s noise as it is to those in high-end resorts by the water. From our hotel balcony, we watch a young family of 5 making their way to the beach at sunset for five nights in a row. They carry sleeping bags and full-strength parkas, woolies, and mittens. Night after night, I see them hunkering down for the night on the beach. Around 7 in the morning, they collect their belongings and make their way back to the comfort of their hotel rooms. Later, I hear that they are protesting the existence of homelessness and the paucity of affordable homes in Hawaii. They are making their statement known, and every night, we hear of similar happenings all over the island.

What was I expecting? After all, I had been to Kauai zero times to Maui’s 8 (the number of times I had visited). We were comfortably ensconced in a roomy hotel overlooking Kanapa Beach, a natural bay where locals from Lihue paddle-boated endlessly. I watched a man paddle boat for hours on end every day. He seemed to be sorting through the chaos of his life as he crisscrossed the bay again and again. There was something repetitive and meditative about his practice, as if through this patterning, he would find a way forward, perhaps in a different direction. This lone man in a lime-green bodysuit typified for me the essence of Kauai—where at once guards with firearms block the multiple entrances of a 1000-acre property while in Hofgaard Park in Waimea, an older man with brown mottled hair lies in an open cot under a tree. We are navigating imperfections all along and as my toenail catches on skin and splatches of blood soaks through my sock, I think of this.