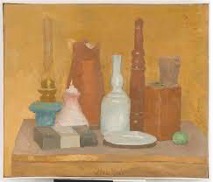

Bottles. Jars. Watering cans with handles. Boxes. Funnels. Pans. Shallow pots. Their exteriors obliterated by paint so thick that they become uniform, even timeless, a forever memento of something that existed a long time ago. Green bottles lushly decorated from Alexandria, Egypt. Red and blue Ovaltine boxes, their labels now varnished with gesso, the O of Ovaltine barely visible. Arrangements and re-arrangements, obsessively done, by line and shape and form, by height and length and width, by volume and density, by tone and color. Who was this Italian artist and what in his imagination led him to paint almost 1300 canvasses and etch on copper plates, mostly still lifes and some landscapes, over five decades of his life?

My memory flashes back to 2009 like a neon traffic light blinking hopelessly on a dark side street in Washington, DC. And just as swiftly, it whiplashes back to Milan in February 2024. It is the spring of 2009, and I am at the Phillips Collection in DC encountering my first ever Morandi. My friend, Judy, plays a part then as she does now. She has forever been this sure-footed master strategist, tracking down rare finds like Morandi’s retrospective in Milan or the house museum of a lesser-known polymath in Turin who worked obsessively on architecture as he did erotica. She masterminds our annual art trips and has a knack of meeting people where they are, curating exquisite art experiences that have haunted our imagination much after they are over. Today, she recounts what we are going to see at the Palazzo Reall, the site of Morandi’s 2024 retrospective in center city Milan. And as a practice run, we see the 40 pieces of Morandi in the collection of the Boschi di Stefano House Museum.

Judy Stein in Milan, 2024. Photo courtesy Anu Mitra

Judy is a hard taskmaster, making sure that we pay attention and take away from every situation what is rightfully ours. But she is as compassionate as she is terrifying. We talk through our thoughts, each person arguing and sometimes revising their point of view. And through this Socratic conversation, we get a better understanding of things. When we started art trips with Judy in the early 2000s, the group coalesced around art. But two decades later and with twentyish art trips under our belt, our friendship has become the funnel through which we understand life and art. Over the years, our heartaches and joys have become the point of change through which we have come to know and recognize our world.Ju

And so it is today. My memories of the Phillips retrospective of Morandi is steeped in a bleary vagueness. My three kids were young in 2009, I was clinging on to the shred of a teaching job at my Cincinnati university, and if I remembered Morandi—it was only through the posters of his jars and bottles that lined major Washington DC thoroughfares.

But today, I have come to Milan prepared to pay attention. Who is this enigmatic artist, I ask myself? What kind of legacy did he leave behind? Even though some artists resist a biographical reading of their art, I personally feel that one is almost impossible without the other. Both life and art are equal measures of a calculus meant to add up to a certain knowing of things. And I promise myself, I will try my hardest to stay away from easily begotten narrative truths. Clear-sightedly, I will try and absorb what the artist is trying to say to me. Right in the heart of Milan in the throb of a bustling city, I remember my heart standing still, my breath quietening and my awareness sinking to a deep place.

An Italian artist who was as interesting as his works, Morandi was born in 1890 in Bologna as the oldest of five boys and three girls. When his father died in 1909, Morandi became the official head of the household. He lived in the same house on Via Fondazza from 1909 to his death in 1964, with his mother and three sisters. He was unceremoniously tucked away in a small bedroom in the back of the house with his studio positioned adjacently by. He only needed to commute a few short steps to work and this intense, reclusive practice, repeated every day for years on end, made Morandi more like a monk. Disciplined and with a single-minded commitment to his craft, Morandi spoke very little but thought a lot more. He worked obsessively, playing with deeply mathematical enigmas that he thought would help unravel for him the philosophical ideas of impermanence, of loss and the elusive hold of memory on our sense of who we are. It was as if what Morandi could not reconcile in his rearrangements of pots and watering cans he could with his philosophical probing and questioning. He did this through his images which became a continuous commentary on the fleeting nature of life and on art’s own swift-footedness. John Berger aptly comments, “Morandi’s project was to observe continuous change without the alibi of meaning.” Morandi shunned the public eye and is thought to have given only two media interviews in his lifetime. No wonder that he was nicknamed El Monaco or the Monk!

Giorgio Morandi’s Bologna house has since become the Museo Morandi, and the Appenine town, Grizzana, where he visited most summers, renamed Grizzana Morandi. Such was his deep rootedness in home and geography that he rarely traveled outside Bologna. In his lifetime, he is known to have visited Florence, Rome, Venice and Milan, and toward the end of his life, Paris.

He came to be associated with various schools of art that sprouted in the early decades of the 20th century: Cubism, Minimalism, Futurism, Metaphysics, and even Abstract art. But he resisted allegiance with any one specific narrative and wanted to exist on his own terms—painting again and again the bunches of still life posies and flowers in the beginning of his career, the Grizzana landscape, and then the bottles and pots and flowering cans till the end of his life. Over his lifetime, his paintings came to be known throughout Europe and the Americas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in their 2008 retrospective writes that in 1934, “in a public address by Roberto Longhi, then Professor of Renaissance Art at the University of Bologna and unofficial cultural czar of Italy, Morandi was recognized as perhaps the greatest living painter in his country.” In 1949 Morandi was featured in the seminal exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and in 1957 he was awarded the Grand Prize for painting (ahead of Jackson Pollock and Marc Chagall) at the São Paulo Biennale in Brazil. Giorgio Morandi died at his home in Bologna on June 18, 1964.

Looking at Morandi’s work today—his lone self-portrait, his flowers, his Cezanne-like cubist landscape—I cannot help but be awestricken by the artist’s self-awareness. Morandi’s images are defined by its dailiness and for being unspectacular. Its focus lies on making the ordinary extraordinary and he is thought to have painted time itself, the slow gradual accumulation of dust settling on objects, of light falling slowly, consistently, predictably, and thereby marking the gradual passing of time itself. Morandi designed his life to honor his artistry. He chose the simple and solitary life—working with clusters and mandalas of arrangements, all of which ultimately led to some sort of clarity that only he could ascertain.

In the end, Morandi’s works are lessons in the complexity that underlies simplicity. His art defies interpretation, even though one can hardly ignore the tight self-restraint that guides his focus. In learning from Giotto and Caravaggio the lessons of volume and weight; the essence of light from Pierro della Francesca; and from Cezanne the glorification of the ordinary, he followed the path of thinking. As he thought through the process of capturing the dailiness of life, Morandi freed up thought itself. His bottles and pots and watering cans transcend form and structure so that in them, and through them, he was able to see himself clearly.

Grateful to you for enhancing my understanding of Morandi. It is the true master who can simultaneously make simple that which is complex while adding complexity to our thoughts on simplicity.

Amy:

What an honor to be cast as a “master” like other great ones. It is indeed a great compliment! Our trip to Northern Italy was memorable because of our encounters with Morandi and Mollino among so many other greats. This is what art and travel does for me! It takes me far away from my own, small suffering to an overview that offers other ways of being in this world. Thank you for being there on the journey with me!